Close to 900MW of publicly announced battery storage projects will be online in continental France by the end of next year and although the country lags behind its nearest northern neighbour, the business case for battery storage is growing.

As shown by the work of our colleagues at Solar Media Market Research, the UK has roughly 1.5GW of large-scale battery storage. Its market has grown rapidly: before a 200MW tender for grid services held by transmission system operator (TSO) National Grid in 2016, the UK had almost nothing.

Now that the ability to stack revenues from multiple streams including ancillary services, arbitrage and the Balancing Mechanism and Capacity Market structures have propelled the UK into something of a leading position among regional markets.

A similar, but different, energy storage market revolution seems imminent in France. We speak with Corentin Baschet, analyst at energy storage consultancy Clean Horizon, on why that is.

Firstly, we should make the distinction between continental France and its various island territories. There is quite a lot renewables-plus-storage on French islands like Guadeloupe and Martinique, from dispatchable renewable energy tenders.

Those represent a small but significant recurring market of course, but within mainland European French borders, there were just a couple of megawatts of commercial installations as recently as 2019, Baschet says. That grew within the past three years to about 300MW.

From tallying figures from publicly announced projects, Clean Horizon has identified that adding together already operational systems along with those announced, or in construction to be completed by 2023 year-end, brings the market to almost 900MW.

This is all the more encouraging because unlike the UK, there are only two revenue streams available for battery storage assets in France today.

One is long-term contracted revenues from the capacity market — France held a dedicated low carbon capacity market auction in 2019, awarding seven-year contracts to winning bidders for 235MW of storage, announced the following year.

The other is frequency control reserve (FCR), aka primary control reserve (PCR), what could be seen as the first rung of the ancillary services ladder. Assets in FCR react to short-term frequency imbalances on the grid within 30 seconds of receiving a grid signal and able to cover up to 15 minutes per incident.

A third revenue stream, automated frequency restoration reserve (aFRR), aka secondary reserve, is expected to open in near future. It had been due to open in November and in fact auctions had begun, but was halted due to the European electricity crisis, which sent prices spiralling upwards.

“The resulting prices were so high that the regulator has asked for the transmission system operator RTE to stop the auction, because it was resulting in too expensive prices,” Baschet says.

“Essentially RTE was paying €155 per megawatt per hour for secondary reserve and procuring about 750MW every single day. That means that we’re talking about millions spent every single day for secondary reserve.”

Previously, the regulated secondary reserve market gave large generators a mandate to provide the grid service at a price defined by the regulator, around €19/MW/hr. Instead, RTE was paying €155 x 24 hours x 750MW = €2.79 million every day, about 10x more than it had been paying under the regulated structure.

“Electricity prices were going through the roof at the same time, and our government was trying to limit the impact of electricity prices,” Baschet says and along with reducing taxes on electricity and locking in prices for end customers, the temporary stop was called to the aFRR auctions.

It is however, tentatively expected to go live once again in July this year. A temporary setback, says Baschet, which hadn’t yet really impacted battery storage — the auctions were so new, no batteries had had time to pre-qualify to participate. However, plenty of battery developers are interested in the potential revenues.

Baschet recently told Energy-Storage.news that battery storage could capture about a third of the opportunity for aFRR across the interconnected European market by 2025.

Unexpected leaders with a ‘peculiar’ business model

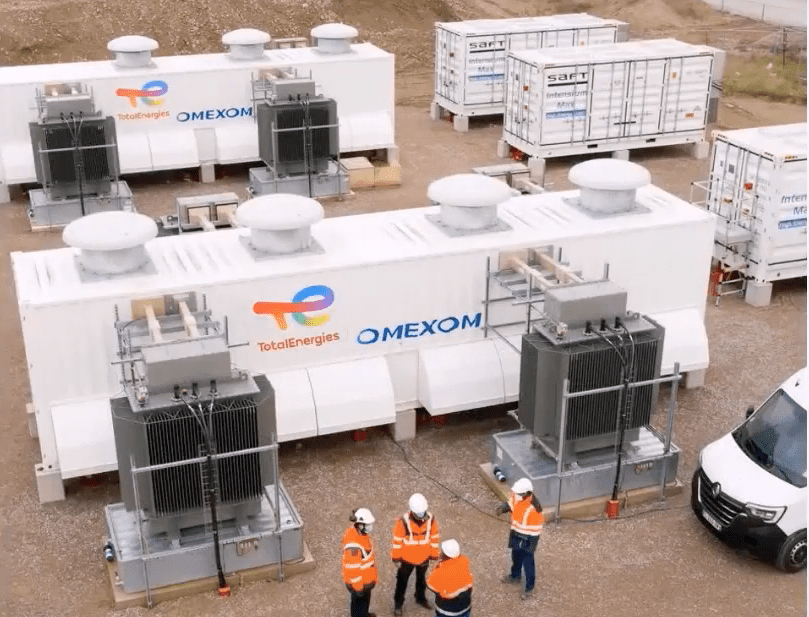

Energy-Storage.news reported a while back on the completion of an expansion at continental France’s largest battery energy storage system (BESS) project. BESS capacity at the TotalEnergies refinery site in Dunkirk, northern France, is now 61MW/61MWh over two phases, with the most recent 36MW/36MWh addition completed shortly before the end of 2021.

The energy major has 103MW of capacity market contracted energy storage online or coming online in France. Interestingly however, despite presiding over the single biggest project in the country, TotalEnergies sits second in Clean Horizon’s chart of France’s most prolific (publicly announced) battery storage project owners and developers.

The leading player is NW Storage, a subsidiary of renewable energy company NW Group and Corentin Baschet points out that the company’s business model is “very peculiar”.

“What they do is that they develop 1MW projects — and they make a lot of them — because they’re planning to have more than 300 built by end of year in continental France.”

Whereas in neighbouring Britain it seems like the average BESS project is closer to 100MW than 1MW today, the business model appears to be to build a lot of smaller assets and then sweat them as much as possible.

NW Storage is a small company but has gone in hard into the energy storage market, Baschet says, and in a leading position despite building only small sites, based on its own modular, plug n play energy storage system solution and often coupled with EV charging.

Pros include the ability to quickly replicate projects from site to site, whereas the downside may be that NW Storage needs to find a lot of sites. But with FCR revenues averaging out at €17.8/MW/hr across 2021, the business case appears to be working.

‘Favourable economics’ but long-term risks to market

“At the moment, it’s very favourable,” says the Clean Horizon analyst, on the economics of battery storage in grid-connected France.

Adding together per-megawatt numbers for typical revenues earned from FCR and capacity market payments of roughly €20,000 per megawatt, close to €170,000 could have been earned last year for each megawatt at a one-hour duration battery storage asset.

Clean Horizon has modelled that in Europe a one-hour duration battery storage system needs to earn about €70,000/MW/yr. In other words, assets made a lot more last year than had been expected by their developers and owners.

On the other hand however, there is still a high market risk long-term. That €170,000 per year is unlikely to remain and earning at least €70,000 each year for the whole 10-15 year lifetime of a battery project is likely to be essential.

“There’s a risk that these revenues shrink in the future, as more and more batteries get deployed. The French market depth for frequency regulation is 500MW. We can actually export some of this capacity, so 500MW is the need in France for FCR; we can export 150MW,” Baschet says.

“So it could be that there’s room for 650MW of batteries providing FCR in France, but once this threshold is reached, we’ll need to find other applications for storage. So hopefully secondary reserve will be open by then.”

Grid operator to launch tenders

Transmission operator RTE has already engaged in some trial activities through which storage is being deployed in continental France.

One is Project Ringo, which gauges the effectiveness of energy storage as a virtual transmission asset. Three energy storage systems totalling 32MW, including two-hour and three-hour duration batteries, act as absorbers of surplus renewable energy on the grid.

The other is a flexibility tender: RTE sought options in four strategic locations where surplus renewable generation and growth in load from EV uptake is causing grid congestion at substations.

At two of those locations, battery storage could be a good fit. However, due to their need to deal with a congested grid first and foremost, it may be difficult to stack revenues from other services for batteries in the technology agnostic tender.

RTE owns and operates assets participating in Project Ringo, but is contracting with developers of projects for flexibility. Project Ringo allowed RTE to experiment with investments into energy storage that it could really dive into and see how the technology works.

What this means longer term is that RTE is expected to use those projects and other findings as the basis for creating storage-dedicated tenders, Baschet says, as enabled by a change in law last year.

These could be for any need RTE can identify for storage on its grid.

“So for now we don’t know what [services RTE will tender for]. It could be anything, but they have the capability of having this storage tender now. It is not any more a flexibility tender to deal with congestion [in which storage can take part], it is really a storage tender. A bit like there was in the long-term capacity market auction, which was really well designed for batteries.”

Another of France’s European neighbours, Belgium, is seeing its market open up for energy storage investment even more quickly and what is striking is the duration of projects. Four-hour duration battery projects are on the way from a number of players.

That is due, Baschet says, to Belgium already introducing its local version of the new pan-European aFRR secondary reserve market — which requires more energy than FCR — as well as better opportunities to do energy trading, and a higher-paid capacity market opportunity.

In France, projects in construction and on the way nearly all remain one-hour, due to the business case for FCR’s shorter discharge requirements. Once aFRR is introduced, some BESS projects with two hours will likely be seen.

However, uncertainty comes from the current supply chain and commodity pricing crunch, especially on lithium carbonate and other battery raw materials. The industry has seen pricing declines slow down before, but it isn’t used to seeing battery prices go up.

“That has adversely impacted a lot of storage projects, which, for instance, were close to making an investment decision and had feedback from system integrators that the price had increased by up to 20% on the DC system part,” Baschet says.

“It’s been increasing the decision time and making the decision-making process more complex, with price variation and raw material impacting the integrators to the vendors and the buyers, because it’s difficult to make investment decisions on a price which is changing every other day.”